For the past month or so I’ve been playing Connections, a new daily word game on the NY Times Games site. It shares structural features with Wordle, in that a new puzzle is released once a day and you can share results in a color-coded format that shows how many tries it took you to reach the solution. The gameplay is pretty simple: you’re presented with a 4 x 4 matrix of words, and the challenge is to create four groups of four words that are connected in a distinct category. Sounds simple enough, but there are enough tricky misdirections, overlaps, and obscure connections to make solving a challenge. Besides being fun, the game prompted a few reflections for me about how we make sense of things and how the way the Web works mirrors how our brains work.

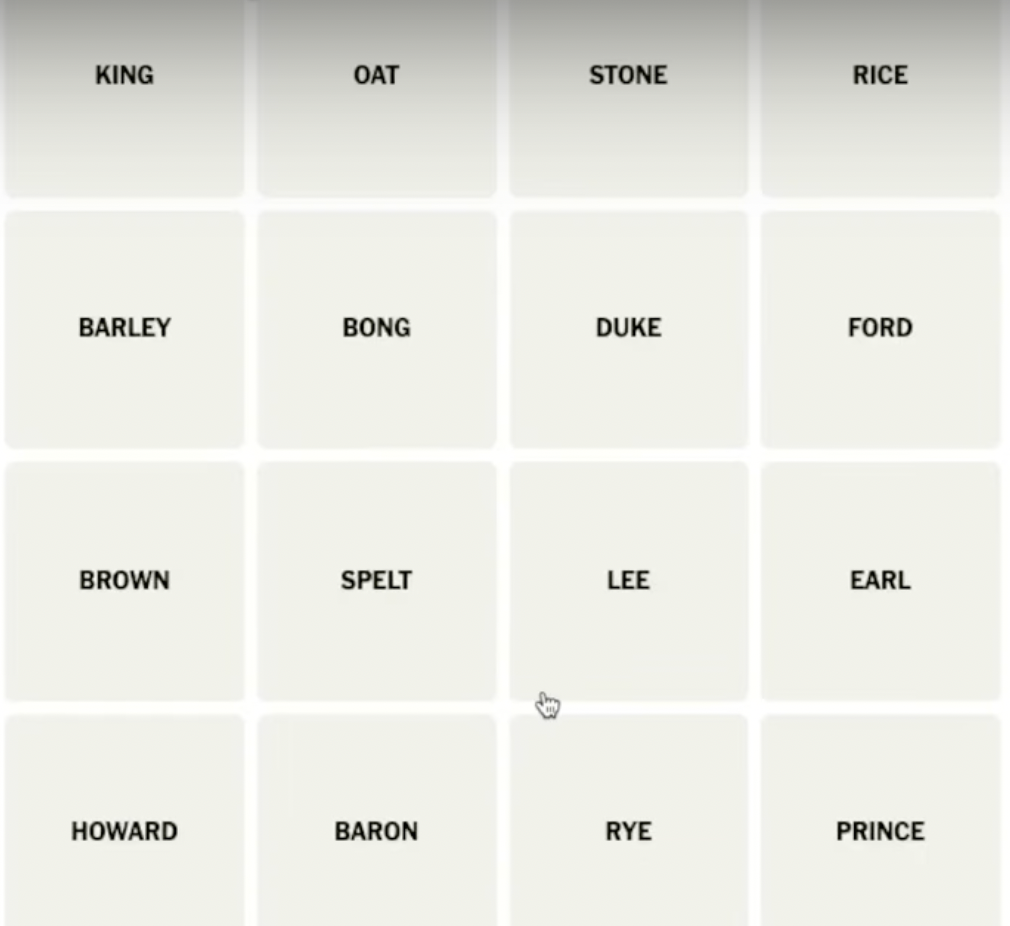

Here’a a recent game board (unsolved, for July 1) that I found a bit tricky. If you want to solve here first, just scroll down far enough to see the grid. At the bottom of this post I’ll reveal the solution and make a few comments about the solving process.

In “How Our New Game, Connections, Is Put Together,” developer Wyna Liu describes the process of constructing the game boards. But the concept for the game is not new. It turns out that there is a British television game show, Only Connect, that has a segment called “Connecting Wall” with the identical format and gameplay. Many game critics and people connected to the UK quiz show, including the host, Victoria Cohen-Mitchell, have criticized the NYT for claiming to have created a unique and original game that seems to replicate, without attribution, a show that has been airing for fifteen years on the BBC. It’s likely that there are even earlier antecedents and other knock-offs as well, including the online game PuzzGrid, which features user-submitted boards (and which attributes Only Connect).

Boardgame aficionados are like familiar with Codenames (there’s also browser and app versions), which employs similar mechanisms to create its gameplay. Codenames also uses a grid (five x five) of words and terms among which players are challenged to find connections. But in this case, the connections are not preexisting; one player on a team (the “spymaster”) states a word, and team members identify words on the grid that connect with that word. So in that sense it’s the inverse of Connections and Only Connect; in Codenames, you’re given the category and then you have to find the members that belong to it.

There also happens to be a test that was developed some years back by cognitive scientists called the Remote Associates Test. This tool was originally developed “to assess a wider range of cognitive abilities thought to underline creative thinking,” although it seems to have fallen out of use more recently. The idea is that one is presented with a series of sets of three “stimulus words,” which, on the surface, do not immediately appear related (thus, they are “remote” from one another). The test-taker must then think of a fourth word that is somehow related to each of the first three words. For example, if given the words, “peppermint, dog, and tree,” the common associate might be “bark.” Proficiency in the remote associates test would serve one well not only as a solver but also as a constructor of word association games.

The underlying principle of all these games and tests seems to be the idea of “associative indexing” (hey, that abbreviates to AI … hmm). Associative indexing is a concept perhaps first proposed by the early web visionary Vannevar Bush in his 1945 article, “As We May Think,” an article widely recognized as foreshadowing the eventual emergence of hyperlinked information and the World Wide Web. Bush recognized a fundamental property of human thought, namely that it is “associative.” Any word, term, or concept presented to or generated in the brain evokes a network of associated words, which is relatively unique to each person. A sequence of such connections forms what Bush termed an “associative trail.”

Bush recognized that our capacity to gain a thorough and comprehensive understanding of a given topic or issue often involves a series of explorations, each one prompted by the previous one, that, taken cumulatively, represents the composition of a framework of knowledge. That’s how our brains seem to function … one thought or idea priming the next. The problem that Bush grappled with was information overload and the overwhelming accumulation of documented material, which was difficult and burdensome to sift through and search. What Bush envisioned with his idea of the “memex” was an external device and system by which the brain could move smoothly from one source, text, document, to other related sources in a series of moves (the “trail”). A half century later, Bush’s vision was largely realized with the advent of hyperlinks and the World Wide Web.

Perhaps the reason we (or at least I) enjoy games like Connections so much is that they exercise this fundamental aspect of our cognitive operations, namely, our capacity to group ideas and concepts according to relationships. There is perhaps much more that can be said as to what this reveals about how we think, and that might be the subject of another post someday. The “categories” that we attempt to discover in Connections or Only Connect invoke the ontological notions articulated, for example by Aristotle (in a more “objective” or metaphysical sense) and Kant (in a more “subjective” or epistemological sense). Admittedly, these sublime philosophical notions may be less in play when the categories presented in the games are “Title TV Doctors” or “Band Names Minus Numbers” (I mean, come on). But even pop culture topics can engage our innate capacity to group like things together.

Word games like Connections call to mind other subfields and concepts of philosophy, cognitive science, and language, such as taxonomy, polysemy, disambiguation, domain knowledge, and lateral thinking. Taxonomies involve systems of classification that organize objects according to similarities of properties, often in a hierarchical arrangement from the general to the specific. Like ontologies, taxonomies employ categories (e.g., animals, vertebrates, mammals, primates, etc.), though with perhaps less attention to the ultimate nature of what a thing is in itself (its ontology). Polysemy refers to the property of language by which words have multiple meanings, senses, or references, often only remotely related. This is just a guess, but it seems the English, among the major world languages, has a particularly high degree of polysemicity. This may be because modern English has absorbed vocabulary from so many distinct languages and culture over the last several hundred years. Polysemy is the basis for many types of word games such as Connections; the interest and challenge comes from disambiguating among the multiple possible senses of a word. Domain knowledge obviously comes in very handy for solving puzzles … I mean, most of the time, you either know something or you don’t, right? Granted, the domains in question for a particular puzzle might not be all that profound (“fictional pirates,” say, or “Monopoly squares”), but everything forms part of the background knowledge of our culture, maybe like the background radiation of the cosmos, perhaps faint but ever present. And solving puzzles prompts us to use lateral thinking in order to approach the unknown from indirect and unconventional paths of inquiry.

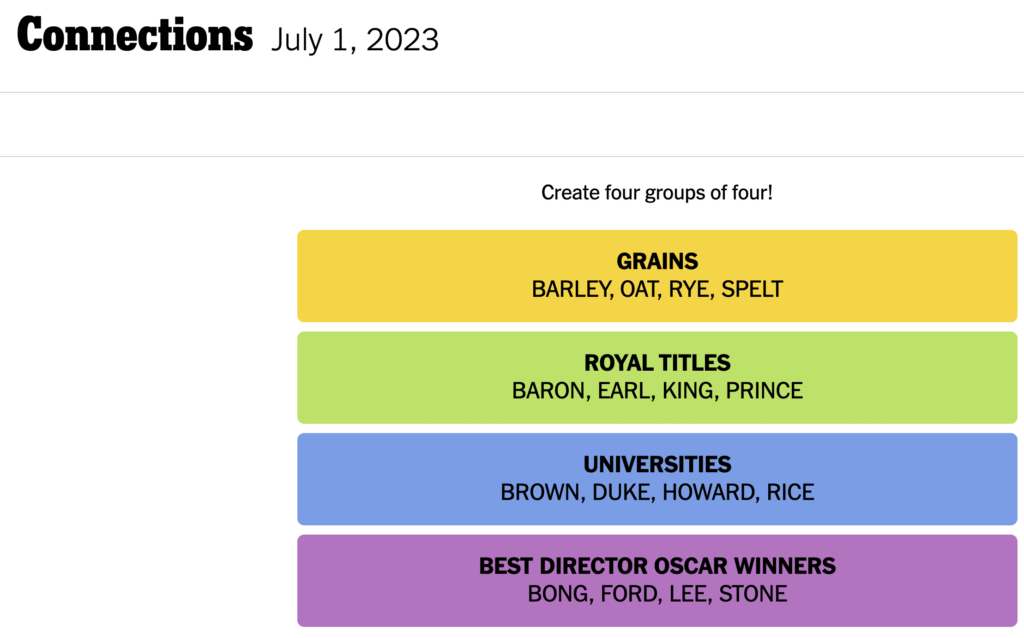

OK, now for that Connections puzzle from July 1. So, one thing to remember is that each puzzle should have a unique solution. That is a constraint that creates a clear expectation for the solver. The initial challenge of the puzzle is not that the words are particularly obscure; actually, a greater degree of ambiguity can be created with more common and unspecialized terms. Rather, a challenge that becomes obvious fairly quickly is that there are some legitimate groupings of more that four terms. Red herrings can flash their polysemy by being a candidate for two or more groups. For example, there are clearly five types of grain, five royal titles, and five movie directors in the grid. But we want groups of four. The first step is to nail down at least one category that can have four and only four members. After putting together those three groups of five, I was just left with the word “brown.” I needed to add one word from each of my three groups of five to go with “brown” … but which ones would they be, and what would be the connection among them?

I rearranged different combinations of words on my scratchpad, and came up short for the longest time. Finally though, as I ran through possible referents for “brown” and looked at the other words, I saw “duke” and “rice,” and the penny dropped. Colleges! Was there one more from the movie director list that could join them? Yes, “Howard” it was. So, they’re “universities” and not “colleges,” but whatever. The disambiguation process was complete, and I had my solution.

It’s worth pointing out that getting the category correctly described is a distinct step beyond identifying the four members that belong to it. In this case, for example, it was not just a group of well known film directors, but a specific group of “best director oscar winners.” It can happen that, after getting the first three groups, the game is basically over, because the contents of the fourth group are obvious. Yes, but it still may not be clear what is the connecting association among those four remaining terms. For example, in this morning’s puzzle (July 7), I was left with “blink, maroon, sum, u” as my final quartet. I had no clue; do you? This turned out to be the aforementioned “Band Names Minus Numbers.” Even after the reveal, I could only identify U2. Obviously not part of my background domain knowledge.

It would be fun to construct these puzzles as well as to solve them. Creating the appropriate level of difficulty for a given audience of solvers can itself be a tricky puzzle. I think as a rule the association among the words should be semantic, and not orthographic (they all contain the letter z!) or phonemic (they all rhyme!), or something like that. But this can be a judgment call. So to date, Connections puzzles have included categories like “Spices that start with ‘C’,” and “Words Spelled with Roman Numerals.” A particularly enjoyable type of category is when all the terms combine with another term in recognizable ways … like “Mr. __” (bean, clean, fox, peanut), or “Sound __” (asleep, barrier, bite, wave).

In case you’re wondering (though you likely aren’t) … there was a band called The Association, which the post title might have primed you to recall. Not just any band but, more specifically, a “sunshine pop” band. So if you ever see a word wall with “Sagittarius,” “Eternity’s Children,” “Peppermint Rainbow,” and “The Left Banke,” you’ll know what you’re dealing with. And, to be sure … these are also all examples of band names that do not include a number.